Trauma

n. Trauma is an intensely distressing experience that, when left untreated and inadequately buffered, overwhelms an individual's nervous system leading to enduring dysregulation of their sense of safety, wellbeing, and ability to function as their authentic self.

Introduction

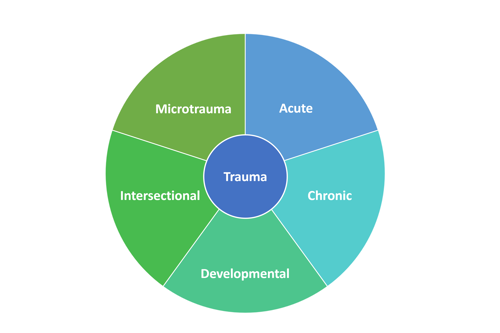

Trauma is a complex and multifaceted experience that profoundly affects individuals' wellbeing and development, often with life-long consequences. Given the criticisms and shortcomings of current classification systems, and to enhance our understanding and address the diverse manifestations of trauma, I propose the Holistic Trauma Classification System (HTCS). This novel system creates five distinct and equal categories with a prefix system: Acute Trauma (A-PTSD), Chronic Trauma (C-PTSD), Developmental Trauma (D-PTSD), Intersectional Trauma (I-PTSD), and the novel concept of Microtrauma (M-PTSD). By recognizing these different forms of trauma, the HTCS provides a comprehensive framework that enables a deeper comprehension of trauma's specific impacts, thereby facilitating tailored supports and interventions.

Criticisms of Current Trauma Classifications

Trauma is a complex and deeply impactful experience that significantly affects individuals' mental and emotional wellbeing. However, the current classification systems for trauma, such as found in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), have faced valid criticisms for oversimplification, limited developmental perspective, inadequate consideration of context, stigmatization, and exclusion of certain traumatic experiences. In response to these concerns, the Holistic Trauma Classification System (HTCS) offers a comprehensive framework that addresses and rectifies these criticisms, providing a more holistic and inclusive understanding of trauma.

Diagnostic Oversimplification

The DSM's diagnostic criteria for trauma-related disorders may oversimplify the diverse and complex nature of traumatic experiences. The HTCS acknowledges the multidimensional aspects of trauma by offering a more comprehensive framework that considers the various dimensions of trauma, including acute, chronic, developmental, intersectional, and microtraumas. By recognizing the different forms and impacts of trauma, the HTCS provides a more accurate representation of individuals' traumatic experiences.

Lack of Developmental Perspective

The current trauma classifications often overlook the developmental aspects of trauma, particularly the unique impacts of traumatic experiences during early stages of life. The HTCS embraces a developmental perspective with Developmental Trauma (D-PTSD), recognizing that trauma experienced in childhood and adolescence can have profound and long-lasting effects on psychological, neurological, and biological development.

Limited Focus on Context

Context plays a vital role in shaping the experience and impact of trauma. The HTCS addresses this concern by emphasizing the importance of considering social, cultural, and environmental contexts in trauma assessment and treatment. It acknowledges that trauma can be influenced by systemic oppression, cultural beliefs, and social support networks. By incorporating a contextual and intersectional lens, the HTCS provides a more holistic understanding of trauma that accounts for the diverse social and cultural factors at play.

Stigmatization and Pathologization

Critics argue that the current trauma classification systems may pathologize individuals who have experienced trauma, perpetuating stigma and a sense of victimhood. The HTCS takes a different approach by shifting the focus from solely emphasizing psychopathology to fostering resilience, growth, and recovery. It recognizes the strengths and adaptive responses individuals develop in the face of trauma, promoting a more empowering and strengths-based perspective. It also shifts the perspective from "What is wrong with you?" to "What happened to you?" which is a far more meaningful question that avoids stigmatization. Lastly, while the HTCS utilizes the existing PTSD acronym (Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder), a patient should never be pathologized as "damaged" or "disordered".

Exclusion of Certain Traumatic Experiences

The current trauma classifications may not fully encompass or adequately address certain types of traumas, such as complex or relational trauma, historical trauma, or cultural trauma, or trauma experienced by refugees, veterans, or survivors of multiple traumas. The HTCS strives for inclusivity by recognizing and validating the wide range of traumatic experiences individuals may face. It acknowledges the unique impacts of these traumas and provides guidance for assessment and intervention approaches that are sensitive to their specific dynamics. Refugees, for example, may have experienced multiple traumas, including Acute, Chronic, and Intersectional. The prefix system built-in to the HTCS also allows for additional experiences, requiring specific approaches and treatments, to be recognized.

By addressing the criticisms of the current trauma classification systems, the Holistic Trauma Classification System (HTCS) offers a more comprehensive and inclusive framework for understanding and addressing trauma. Through its focus on multidimensional trauma types, developmental perspective, contextual considerations, empowerment, and inclusivity, the HTCS provides a valuable tool for professionals in therapeutic and trauma-informed care settings to better support individuals who have experienced trauma. The HTCS also provides a valuable tool for individuals who want to better understand their own struggles and challenges.

The Holistic Trauma Classification System (HTCM)

1. Acute Trauma (A-PTSD)

Acute Trauma, or A-PTSD within the HTCS, refers to horrific and sudden instances of attack, violation, neglect, abandonment, and other severe acute harm. Sometimes referred to as shock trauma, examples of A-PTSD include natural disasters, terrorism, acute instances in war, assault and battery, rape, and witnessing murder. This type of trauma is characterized by its sudden and overwhelming nature, often leading to a range of immediate and intense symptoms.

Individuals who have experienced A-PTSD may exhibit symptoms such as intrusive memories, flashbacks, intense physiological reactions (e.g., increased heart rate, sweating), hypervigilance, and avoidance behaviors including dissociation. Changes in mood and cognition, including negative thoughts, difficulty concentrating, emotional numbing, and nightmares are also common. The impact of acute trauma can be pervasive, affecting multiple domains of an individual's life including their relationships, work, and overall wellbeing.

Early intervention and trauma-informed care are vital in supporting individuals who have experienced A-PTSD. Providing a safe and empathetic environment, validating their experiences, and offering evidence-based treatments such as trauma-focused therapy can help individuals navigate the aftermath of acute trauma and promote their healing and recovery.

2. Chronic Trauma (C-PTSD)

Chronic Trauma, or C-PTSD within the HTCS, refers to trauma that occurs repeatedly and cumulatively over a prolonged period, often within specific relationships and contexts. This form of trauma can result from prolonged or repetitive exposures to traumatic events where individuals perceive few or no chances to escape. Examples of C-PTSD include intimate partner violence, prolonged domestic violence, labor or sex trafficking, narcissistic or authoritarian control, frequent community violence, prisoners of war, or cult or religious abuse.

Chronic trauma can have profound and enduring effects on an individual's wellbeing. Symptoms of C-PTSD may manifest as difficulties with emotion regulation, persistent feelings of fear and vulnerability, distorted self-perceptions, difficulties in forming and maintaining relationships, and disruptions in self-identity and self-confidence. Individuals who have experienced C-PTSD may also exhibit somatic symptoms such as chronic pain, gastrointestinal issues, and sleep disturbances.

Understanding the dynamics of chronic trauma is crucial in providing comprehensive and trauma-informed care. This involves creating a safe and non-judgmental space for individuals to share their experiences, promoting emotional regulation and resilience, and offering evidence-based therapies like somatic therapy that address the complex effects of chronic trauma. Additionally, building supportive and empowering relationships with safe-enough, healthy-enough people can play a crucial role in fostering healing and recovery.

3. Developmental Trauma (D-PTSD)

Developmental Trauma, or D-PTSD within the HTCS, encompasses Chronic Trauma that occurs during childhood, particularly during the formative years of development. This type of trauma can significantly impact a child's emotional, cognitive, and social development, harming their lifelong wellbeing. Adverse experiences such as neglect, physical or sexual abuse, witnessing domestic violence, and parental substance abuse are examples of D-PTSD.

Children who have experienced developmental trauma may exhibit a range of symptoms that differ from those seen in adults. These symptoms can include difficulties with emotion regulation, impaired social interactions and attachments, cognitive delays, poor self-esteem, behavioral problems, and academic challenges. The effects of developmental trauma can extend into adulthood, impacting individuals' mental health, relationships, and overall life satisfaction.

Therapeutic interventions for developmental trauma require a comprehensive understanding of the intricate interactions between trauma and development. Creating trauma-informed environments, providing nurturing and consistent relationships, and utilizing evidence-based interventions such as play therapy, attachment-based therapy, and other trauma-focused therapy can support children in their healing and progression in healthy development.

4. Intersection Trauma (I-PTSD)

In the context of Intersectional Trauma, or I-PTSD within the HTCS, individuals may experience the cumulative effects of intersectional traumas including cultural, racial, gender, historical, and disability-related trauma. Intersectional Trauma highlights the importance of considering the intersections of various social identities and the ways in which they shape an individual's experience of trauma. It encourages a more comprehensive and inclusive approach to trauma-informed care and support. By recognizing and addressing the specific challenges and needs faced by individuals who experience Intersectional Trauma, practitioners can provide more targeted and effective interventions to promote healing and resilience.

In therapeutic settings, addressing Intersectional Trauma requires a culturally sensitive and intersectional approach. This involves creating a safe and inclusive space that validates and acknowledges the unique experiences of individuals with intersecting identities. It requires practitioners to have an awareness of the historical, social, and other contexts that contribute to Intersectional Trauma and to adopt trauma-informed practices that account for the specific needs of diverse populations. Integrating principles of cultural competence, trauma sensitivity, and social justice can enhance the effectiveness of interventions and support the healing process for individuals affected by Intersectional Trauma.

Intersectional Trauma recognizes the compounded effects of multiple social identities. It emphasizes the importance of considering the intersections of race, culture, history, gender, disability, and other factors in understanding and addressing trauma experiences. By integrating an intersectional lens into trauma-informed care, practitioners can better support individuals affected by Intersectional Trauma and promote healing, resilience, and empowerment.

5. Microtrauma (M-PTSD)

Microtrauma

n. Single, individual interactions, often subtle and subjectively experienced, that convey a lack of safety and validation to one's authentic self.

Microtrauma, or M-PTSD and introduced as a novel concept within the HTCS, encompass a wide range of subtle, subjective experiences that convey a lack of safety and validation to one's authentic emotional, cognitive, psychological, personality, agency-related, and other aspects of self. These seemingly insignificant interactions, when recurring or accumulated over time, can significantly impact an individual's well-being and development. By recognizing and comprehending the spectrum of microtraumas, we can better understand their effects on children and adults alike, shedding light on the complex nature of these often-overlooked adverse experiences.

Understanding the Microtrauma Experience

Microtraumas manifest in various forms and contexts, impacting emotional, cognitive, psychological, personality, agency-related, and other facets of an individual's sense of self. Within the realm of childhood experiences, invalidating emotions, criticism, conditional love and acceptance, neglect, lack of validation, over-control, double standards, emotional manipulation, aggression, neglect of boundaries, bullying, and social exclusion all contribute to the microtraumatic landscape. Similarly, in adulthood, microtraumas arise through similar dynamics, including emotional invalidation, criticism, conditional acceptance, boundary violations, microaggressions, and unresolved conflicts or traumas. From an intersectional perspective, microtraumas can also be acts of microaggression, racial or ableist slurs, misogyny, sexism, and other individual attacks on an individual's identity.

The Cumulative Impact

While microtraumas may appear insignificant in isolation, their cumulative impact can be substantial. Children, in particular, are biologically predisposed to prioritize their connection with caregivers over their authentic selves. Consequently, when faced with repeated microtraumatic experiences, they may instinctively sacrifice their own needs and authenticity to preserve the caregiver-child relationship. The cumulative effect of these experiences can be inherently traumatic, shaping the child's self-perception and their ability to express themselves authentically.

Implications for Child Development

Microtraumas can have lasting implications for a child's emotional, cognitive, and social development, and contribute to a complex interplay that may impact the child's well-being, attachment formation, and overall development.

Children are biologically inclined to prioritize their relationship with caregivers over their relationship with their authentic selves. To maintain connection and safety, children unconsciously sacrifice their own needs and authenticity. When children face criticism, belittlement, or demeaning treatment, they lack the cognitive ability to understand that they are not at fault, and they are never responsible for the way the adults in their life act towards them. Their primary concern is preserving the caregiver-child relationship, leading them to alter their thoughts, feelings, and behavior, and denying their authentic selves in order to maintain base safety and met needs. This denial of self is inherently traumatic.

For instance, during the developmental stage of children between three-and-a-half to four-and-a-half years old, their capacity for self-regulation has not yet begun to develop. They rely entirely on their caregivers for co-regulation, healthy attachment, and comfort and soothing. However, some caregivers may not recognize the child's limitations and mistakenly punish them for behaviors or emotions they are not yet capable of managing. The child receives messages that their feelings and emotions are not safe, and that acceptance and love are conditional. Over time, these messages create an environment where the child feels unsafe expressing their authentic self.

Some examples of the negative messages a child may receive from Microtrauma include:

- Inadequacy: The child may internalize the belief that they are inadequate or incompetent because they are being reprimanded for developmentally appropriate behavior or something they are not capable of controlling yet. This can lead to a diminished sense of self-worth and confidence.

- Misunderstood Emotions: Children are still learning to recognize and manage their emotions. If they are punished for expressing emotions they can't fully understand or regulate, they may feel misunderstood and confused about their own emotional experiences leading to life-long emotional challenges.

- Fear of Rejection: When caregivers punish a child for behaviors or emotions they don't have the capacity to manage yet, it conveys the message that their acceptance and love are conditional upon meeting certain expectations. The child may develop a fear of rejection or people-pleasing tendencies and strive to suppress or hide their true emotions leading to difficulties in forming healthy attachments and trusting relationships.

- Inhibition of Emotional Expression: Punishment for natural emotional responses can discourage the child from expressing their feelings openly. They may learn to suppress or deny their emotions, which can hinder their emotional development and create difficulties in managing emotions later in life.

- Avoidance of Risk-Taking and Exploration: Children are naturally curious and explorative. Punishment for behaviors that are appropriate for their developmental stage may discourage them from engaging in new experiences, as they fear negative consequences. This can limit their learning opportunities and hinder their cognitive and social development.

- Perceived Lack of Safety: When a child is punished for their natural developmental stage, it can create a sense of insecurity and lack of safety in their environment. They may begin to associate negative emotions with punishment, leading to a reluctance to express themselves or seek support when needed.

Unveiling the Microtrauma Landscape in Adulthood

While microtraumas are especially detrimental to children, they also leave an imprint on adult experiences. Adults who have encountered microtraumas may exhibit feelings of inadequacy, struggle with emotional understanding and expression, fear rejection, inhibit their authentic selves, avoid taking risks, and carry a sense of insecurity within themselves. These dynamics influence their relationships, personal growth, and overall wellbeing.

Creating Healing Environments

Recognizing the significance of microtraumas is paramount to fostering healing and growth. By creating nurturing environments that prioritize safety, validation, and acceptance, we can mitigate the harmful effects of microtraumas. Practitioners, caregivers, and individuals themselves can play a pivotal role in offering appropriate guidance, support, and therapeutic interventions to address the impact of microtraumas and promote resilience and wellbeing.

A Note for Caregivers

If you are a parent, guardian, or caregiver, it is understandable if you might feel overwhelmed by the concept of microtraumas. Parenting already comes with more than its fair share of shame and guilt, both from within and from societal pressures. The intention here is not to add to that burden. We all make mistakes and have moments where we reach our limits. I, too, have experienced times where I've lost my cool with a child. The good news is that we don't have to get it right 100% of the time. Instead of focusing on the harm that may have been done, it's important to prioritize learning and growth. The key lies in the process of repair, which not only addresses the immediate impact on their nervous system and helps to restore the relationship, but also models healthy conflict resolution for children. What matters most is how we follow up with them afterwards. It's crucial to let them know that it was not their fault, that they did nothing wrong, and that we take responsibility for our mistakes. We commit to doing the necessary work to improve ourselves in the future because they deserve to be treated with respect. By engaging in this repair process, we demonstrate the value of open communication, accountability, and the importance of resolving conflicts in a healthy and respectful manner. We also provide a buffer against the internalization of negative messages the child may have received. In the realm of chronic and developmental traumas, the true injury lies not in making a mistake but in failing to buffer and repair that mistake afterwards. Through repair, we cultivate a foundation for stronger relationships and healthier relational skills.

Summary of Microtraumas

Microtraumas, although subtle, should not be underestimated in their potential impact on individuals. By acknowledging the spectrum of microtraumas experienced during childhood and adulthood, we can foster a greater understanding of the complex interplay between these adverse experiences and well-being. Empowered with this knowledge, we can create environments that validate and support individuals' authentic selves, fostering healing and promoting resilience in the face of microtraumatic adversity. Nurturing healthy attachment relationships, providing emotional support, and validating an individual's authentic self are essential steps in mitigating the harmful effects of microtrauma and promoting overall wellbeing and ability to thrive in life. Understanding the impact of individual microtraumatic experiences, we can become more attuned to individuals' subtle signs of distress and create environments that foster safety, validation, appropriate guidance and support, and acceptance.

Multidimensional Perspective of the HTCS

Trauma is a deeply personal and complex experience that can manifest in various ways. While the Holistic Trauma Classification System (HTCS) offers a comprehensive framework for understanding and categorizing different types of traumas, it is important to acknowledge that not all traumas will fit perfectly into predefined categories. There are instances where an individual's trauma may present unique characteristics or defy easy classification.

In some cases, an individual's trauma may encompass a combination of different types of traumas, making it challenging to assign it to a single category. These experiences may involve complex layers and intersecting factors that require a nuanced understanding. Additionally, cultural, societal, or historical influences may shape an individual's trauma in ways that cannot be neatly captured within the existing classification system. In such situations, I propose it is worth considering a multi-prefix approach, such as ACI-PTSD (Acute, Chronic, Intersectional), to account for the complex nature of the trauma. This flexible approach allows for ongoing refinement and expansion of the classification system to better capture the diverse range of traumatic experiences.

In the future, we may also consider expanding the HTCS to include various additional categories. These new categories would allow practitioners to offer specialized support, prevention strategies, and evidence-based interventions for individuals who have experienced specific types of traumas. Some potential categories might include:

- Environmental Trauma (E-PTSD): Traumas from natural disasters, environmental crises, or related events. Includes experiences like surviving earthquakes, hurricanes, wildfires, floods, and traumas linked to environmental degradation, pollution, climate change impacts, or displacement due to environmental factors.

- Gender Trauma (G-PTSD): Traumas related to gender identity and expression. It may include experiences such as discrimination, harassment, violence, or marginalization based on one's gender.

- Health and Medical Trauma (H-PTSD): Traumas associated with health and medical experiences. This includes including acute and chronic health conditions, medical errors, complications, traumatic childbirth, serious illnesses, prolonged hospitalizations, and the psychological impact of invasive procedures. It addresses the unique needs of individuals with chronic health issues or traumatic medical experiences, offering tailored support and evidence-based interventions.

- Policing Trauma (P-PTSD): Traumas resulting from interactions with law enforcement or experiences within the legal or carceral system. It may involve incidents of police violence, wrongful arrest, racial profiling, prison violence, or other forms of trauma associated with the policing system.

- Religious Trauma (R-PTSD): Traumas linked to religious beliefs, practices, or institutions. It involves distress, harm, or negative psychological effects stemming from one's religious upbringing, community, or interactions with religious authorities. This includes religious abuse, coercion, strict dogma, spiritual manipulation, and other trauma within religious contexts.

- Sexual Trauma (S-PTSD): Traumas related to sexual assault, abuse, or harassment. It encompasses experiences of non-consensual sexual acts, sexual violence, exploitation, or any other form of trauma with a sexual component.

- Technological Trauma (T-PTSD): Traumas resulting from digital experiences, technological interactions, or online platforms. It encompasses experiences such as cyberbullying, online harassment, identity theft, revenge porn, exposure to graphic or disturbing content, or the psychological impact of excessive screen time and social media use.

- Workplace Trauma (W-PTSD): Traumas that occur in the workplace. It encompasses various work-related incidents that may cause distress, such as workplace accidents, bullying, mobbing, discrimination, or high-stress environments that lead to psychological harm.

- Unspecified (U-PTSD): This category applies when a comprehensive diagnosis is pending or when the experienced trauma does not neatly fit into the existing categories. It serves as a temporary classification until a more specific categorization can be determined or when the nature of the trauma is not easily classified within the current framework.

It is worth noting that even today, there are specialized practitioners who are focused on each of these distinct categories.

Overall, it is crucial for mental health professionals and practitioners in trauma-informed care to approach each person's trauma with an open mind and a willingness to listen and understand their unique experiences. They should be prepared to adapt their approach and interventions to address the individuality of each person's trauma journey. By recognizing the complexity and diversity of traumatic experiences, professionals can ensure that individuals receive the support, validation, and care they need to navigate their healing process.

Ultimately, the goal is to create a trauma-informed environment that respects and honors the unique nature of each person's trauma, regardless of where it fits into the HTCM. This inclusive approach allows for a more holistic understanding of trauma and promotes individualized support that recognizes the complexity and diversity of human experiences.

Conclusion

The Holistic Trauma Classification System (HTCS) provides a comprehensive framework for understanding and addressing trauma by introducing categorical representations of the trauma human beings experience. Each classification encompasses unique experiences, symptoms, and impacts on individuals' lives. By recognizing the specific type of trauma individuals have experienced, the HTCS enables tailored support, prevention strategies, and evidence-based interventions. This comprehensive understanding of trauma promotes healing, resilience, and the creation of trauma-informed environments that foster wellbeing and recovery.

Next Steps

In this article, I present the Holistic Trauma Classification System (HTCS) as a proposal for a comprehensive framework to categorize and understand trauma experiences. It is important to note that the HTCS is still in its developmental stage, and I recognize the value of constructive feedback and comments from scholars, researchers, and readers alike. I welcome the opportunity to engage in a meaningful dialogue to refine and enhance this classification system. Your insights and critique are essential in shaping the future direction of this work, and I eagerly invite you to contribute your perspectives to further strengthen the HTCS and its potential applications.